DLAR: What does the phrase Ghost Train Orchestra mean to you personally? Why that name?

BRIAN: Well, the name came from our origin, where I tended to open the show on harmonica. That’s where the train sound comes in. At that time, we had a ghostly wail over the whole thing, played by a saw player — she would bend it and it would create this theremin-esque voice over the top of the reed section. The name appeared that way. Very early on, the band started in the realm of pre-war jazz from the late 1920s, but in the very beginning, we always thought we would move in a lot of different directions, so I think the name also gives you a picture into other worlds. We’re doing a record now called Cities, which is inspired by cities all over the world. So, yeah, travel is a big part of the music.

DLAR: There’s an aspect also of travel that’s like, I see you and the group as walking the line between historians and artists. What is it like to try and preserve something, but also be inventive and reimagining it? Do those things conflict?

BRIAN: For us, it goes hand in hand. We had no interest in recreating anything, so we’re interested in not only paying tribute, but also bringing something new into the music. Our last two records have been collaborations – one was with the Kronos Quartet [The Music of Moondog] and the other one was with David Byrne [Who Is The Sky?], and in doing the Moondog record, we did find a lot of music that wasn’t released yet. So there’s a historical aspect to some of the music, but not all, and we’re moving in a direction that happens to be more new music and original compositions.

DLAR: You have always collaborated with outside artists, but in recent years, it’s clear that you are spending a lot of studio time with other artists like David Byrne, Kronos, Joan As Police Woman, Rufus Wainwright — all of these big names. Is there something that you feel has changed about the band’s process? Maybe; what has been learned about collaboration or shared vision in that time?

BRIAN: Working with David Harrington of Kronos Quartet, for example, was a real life-changer because he became a close friend and I learned a lot about how to approach a record and how to mix a record from him. He has such an attention to detail and a vast knowledge of music that he had so many incredible ideas.

Everyone we work with, you learn something new, so the more people we can work with, the better. I learned a lot from working with Joan As Police Woman, just seeing her come in and perform with us… The virtuosity she brings to the show is such an incredible inspiration for me as a singer. I love watching her perform and seeing her really raise the bar for everyone else.

The recording process is a whole other experience. Working with Jarvis Cocker in the studio, he brought his own thing to that performance. I don’t think he used any of the ideas I had (laughs), but his ideas were so much more imaginative and so much more interesting than anything that I came up with. So I learned that if someone is coming in with those kinds of ideas, the best thing to do is just, you know, let them fly.

There’s so many aspects to music. There’s recording, there’s mixing, there’s performance, there’s writing. I’m collaborating with people in the Ghost Train Orchestra, too. Everybody’s bringing new compositions and new arrangements in, so I’m constantly amazed. There’s this healthy competition that happens when somebody brings in a piece and everyone’s just blown away, and then you have to present your piece.

DLAR: Well, and even before that, all of the process that you mentioned – I mean, Moondog was prolific. What was it like to try and select the pieces that were going to be on that album?

BRIAN: That was hard. We recorded over five days, and at the end, I think we had about fifty pieces recorded, maybe forty. We recorded so many pieces that we probably have three records worth of material. We only released one, and we’re working on a second one now. How do we show the breadth of his music? A lot of records will focus on just string quartet, or just orchestra. We wanted to show all of it — the acapella, the songs — he was such a great lyrical writer.

And then, of course, being able to perform it is really fun because you’re performing as a string quartet, as a jazz orchestra, as a percussion ensemble. You’re not really a jazz band at all when you’re performing that music.

DLAR: From outside of the group, there is almost a dramatic split between people who were shocked that they had never heard of Moondog before [the record came out], and then people who already had this tremendous warm feeling or great familiarity with his work. I’m curious to know how you first became acquainted with his music and what compelled you to say, “We’ve got to follow this thread.”

BRIAN: About twenty years ago, a friend of mine named Bryce Goggin, who was a recording engineer in New York, wrote me a one-line email, saying, “Have you ever heard of Moondog?” I had just started Ghost Train Orchestra, and had mentioned this to Bryce — I said, “Yeah, I’ve got this new group and we’re trying to figure out what directions we want to move in.” And so he wrote this email.

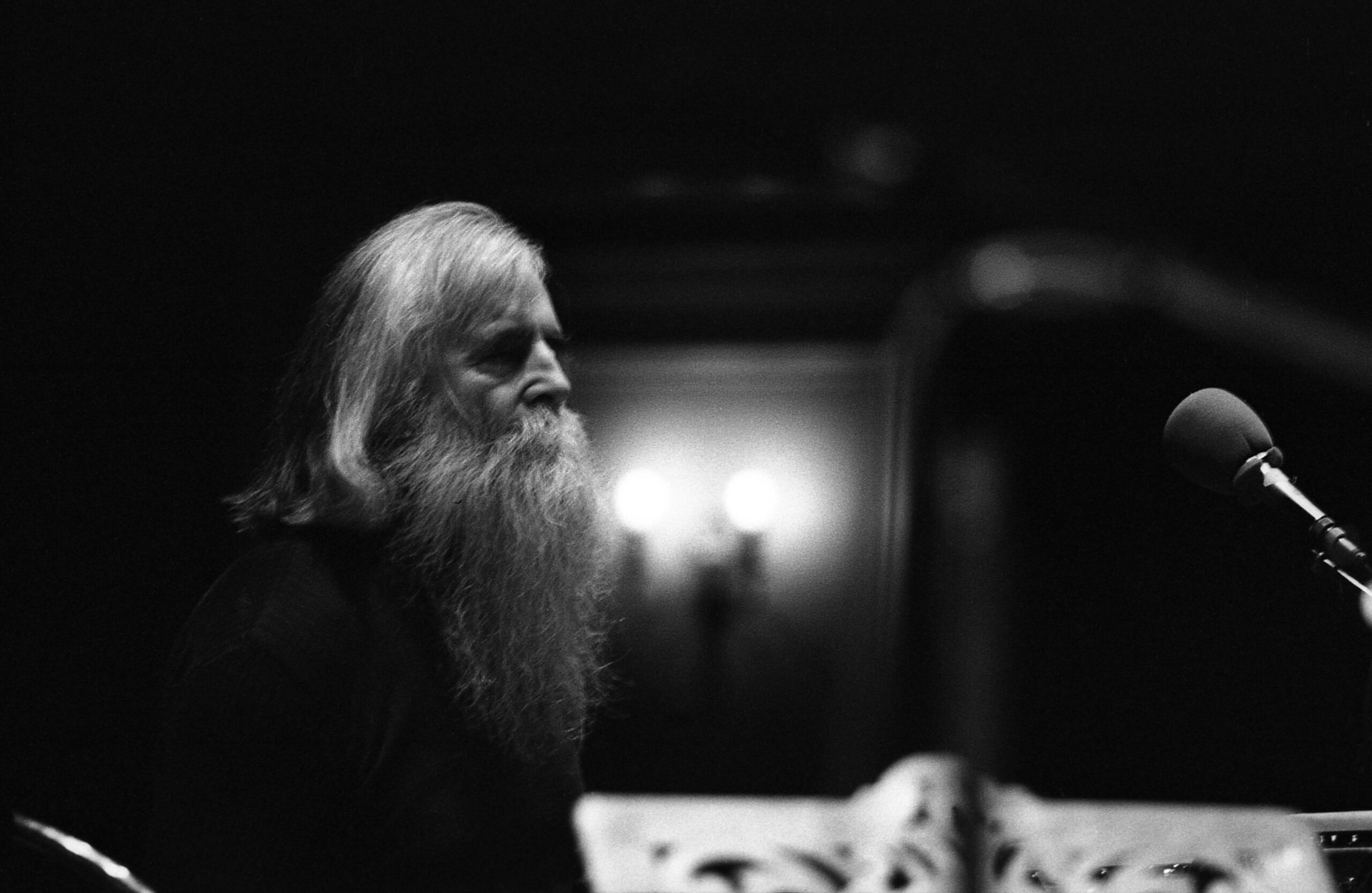

The first record I heard was the 1969 record Moondog, where he has the big beard, and the headdress and the spear and everything. I thought, “Who is this?” Looking at the record cover, it looks like this medieval character, you know? Then I heard the first track, and he immediately takes you into a whole world with that theme song. It was just so unusual — clearly a forerunner of minimalism in its repetitive aspects, but there were also cannons, and beautiful madrigals. I thought this might be a really interesting way to go.

First of all, there was no New York band playing the material. And Moondog was such a New York presence for so many decades that it felt like there should be a New York band performing the music, and that we should be the ones to do it, because the band has so many backgrounds in so many different kinds of music. It was an opportunity to have a larger group of people arranging pieces, which made it everybody’s band. It wasn’t just my band, it was everyone’s band.

The only people who knew who he was were the rock musicians. The rock musicians knew who he was because he’s this outsider artist, right? He’s this cool outsider artist figure, like a Jandek, or a Harry Partch, or Sun Ra, or something like that. Very few musicians I knew working in the classical or jazz fields knew who he was, so this felt like another extension of what we were doing anyway — reimagining and revitalizing composers who no one had heard of.

DLAR: Before we wrap up, are there any upcoming projects or shows that you would like to tout?

Two big shows! One is November 7th at Roulette, where we’re debuting our new project called Cities — it’s all new music written by members of Ghost Train Orchestra and inspired by cities around the world. A music travelogue.

We’ll also be performing at Big Ears Festival in March with the Moondog project, and we’ll have several special guest vocalists — Joan As Police Woman will be with us, Karen Mantler will be with us, and probably a lot more, too, if schedules align. We’re super excited, since we’ve never performed that show outside of New York, so this will be big.