DLAR: Balloon Dog is a pretty playful title for a play that’s grounded in some serious and meaningful themes. How did that name come to be?

JL: There’s a character in the story who makes balloon dogs for a five-year-old girl, so it comes out of the script, but he only started making balloon dogs very late in our creative process. [Jacob] should talk about why not to call it Kabuliwallah.

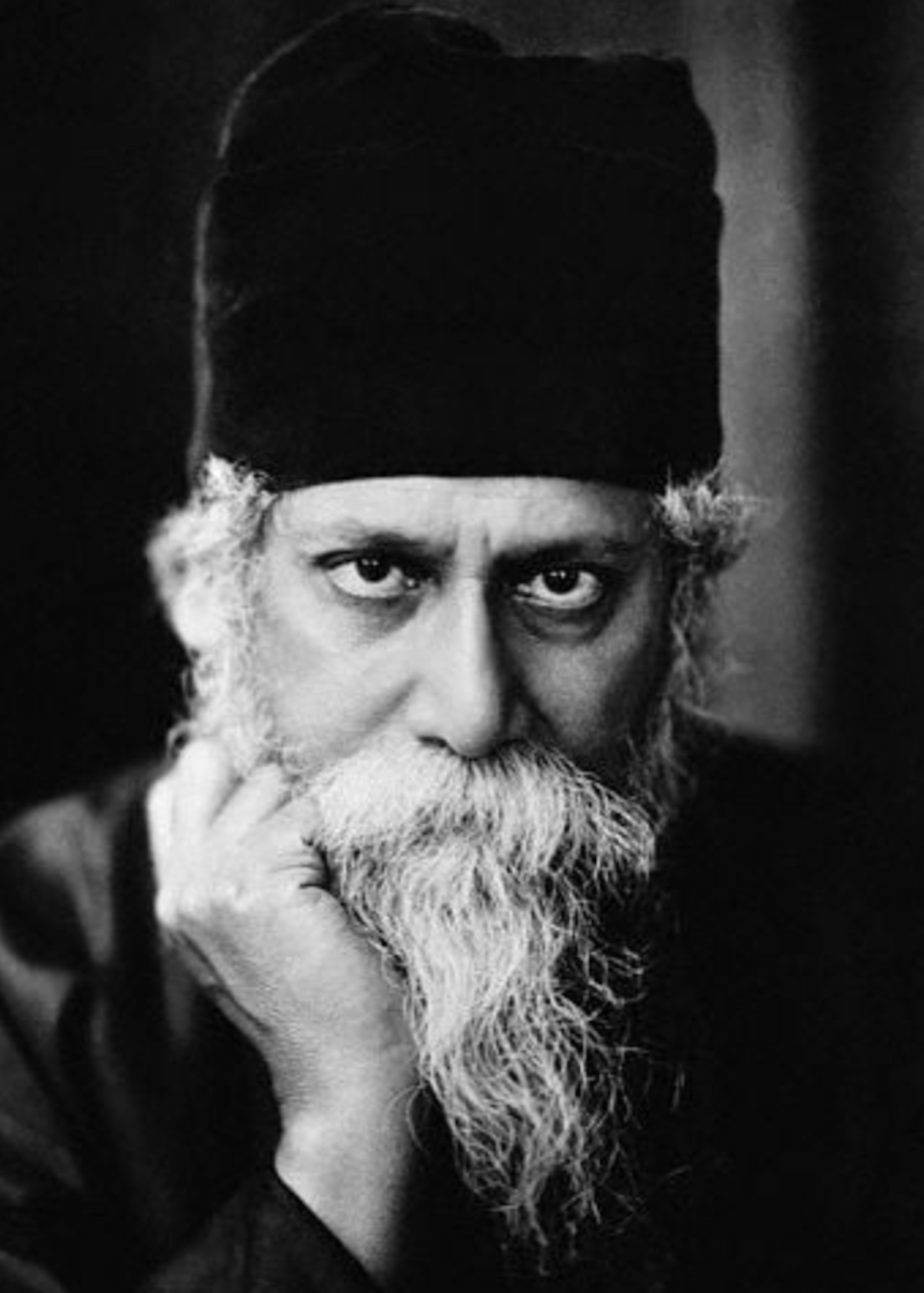

JR: I mean, I love the title Kabuliwallah, and that is the source material, a short story by Rabindranath Tagore. But that story is very much loved by my community. It’s studied at school, like To Kill a Mockingbird or something like that. To call [the play] Kabuliwallah, yes, honors the source material, but also wrong-foots my community when they come along to see it and they’re not seeing what they expect. This is a modern adaptation, a contemporary reimagining of the story. Although we’d hope the heart of the story is the same as Kabuliwallah, it is definitely its own thing.

JL: As you started talking about the heavy content of the material and the light and playful title, it got me thinking about how I was listening to a guy talking about the Irish Potato Famine, and he was saying, “Actually, there’s not much storytelling. You know, Ireland’s a nation of writers and storytellers, right? There’s not many stories about the Potato Famine. Part of the reason is that for those people who were kicked off their land, the experience was so awful and they really had no choice. When we go to see a drama or a story, we’re looking at characters who have choice. Their situation was so awful, that it can be almost distasteful to make drama out of it. I think that for [Tagore’s] migrant worker from Afghanistan, who we’ve translated into an Indian migrant worker in New Zealand … they don’t have choices. This piece is a sideways look at that experience, where the choices actually sit with the people like me and Jake, who are middle-class and engaging with them. The weight of the story shifts over to that sort of place.

DLAR: I feel like it is probably easy for me to ask you about the issues of migration, but I want to ask: what did working on the project allow you to envision about how migration could be or how we could treat each other in the future?

JR: As part of the research for this, I interviewed a bunch of migrant workers here. The stories are so unbelievable in terms of the terrible situation. To put it on stage would just shut people down, I think. The only way to address this stuff is through policy, and I think that is better served by journalism or by documentary. Like Justin said, it’s a sideways look at that stuff with our audience: “How are you complicit in this? How are you seeing other people? How are you othering people?” That’s the gist of where our middle class family — who’s now been confronted by this person who’s formed a friendship with their daughter — that’s the position they’re in. “How do I recognize you as more similar to me than different, actually?” Because that’s the beginning of trying to really see people, you know, not to be overwhelmed by scrolling on your YouTube, but just to be able to look at people as more similar than they are different. And then the big stuff happens with terrible immigration laws, terrible things around visas. All of that needs pressure on politicians to make changes.

JL: What we can do with theater is get people to be asking the questions. We can’t provide the answers, but get people to be asking the questions of themselves and of the world around them. “Why is this like this?” It would be awful to make a play that offered a neat solution for people, tied up in a bow that they could walk away with and go, “Oh, problem solved. I don’t have to think about it.”

DLAR: I also was very curious that the source material and the play that you’re adapting, they both center on the friendship between this migrant worker and a young child. What do you think can be achieved narratively when you’re considering a child’s perspective, compared to an adult’s perspective, on an issue?

JL: Obviously the child’s perspective can bring a kind of innocence, and the ability to see something fresh and without a whole lot of judgment. That’s how the five-year-old girl sees this migrant worker — she’s free of the judgments, fears and anxieties that the adults around her have. She just wants a friend who will talk with her and tell jokes. Narratively, that’s what the child is — the one who really sees him before anyone else really sees him. It takes the adults until the end of the play to see him.

The other thing about the play that I like, the source material is told from the perspective of the grandfather. The point of view of the teller is not the point of view of the child. The teller thinks the subject of the story is this foreigner and his granddaughter, but actually he’s the subject of the story because he’s the one that has to start to see things differently.

JR: The child is also what’s at stake for everyone. We put so much on children with our anxieties and fears, and we as playwrights had to navigate a very tricky dance between, “Yes, the child has this friendship, but the mother is rightly worried about a stranger.” We’re not condoning that children play with whoever they want. Everybody has a stake, and nobody’s wrong, as such, that’s the trick. It’s very easy to write these people off as “Karens;” that would be easy. As playwrights we can do that too — can write caricature. And maybe that’s the place that we start, but through the course of the play, we understand that everybody has real skin in the game, and that’s what makes the choices difficult.

DLAR: I love the idea of starting with the caricature because that allows you to start assuming that along the way you’re going to deconstruct that as it goes deeper.

JR: And I mean, ultimately, I think what we hope is that they’ll be a mirror, that the audience will see themselves in these people. They might be going, “Whoops, I might have felt that way myself.”

JL: I don’t know what you think, Jake, but for me, some of these characters are the closest to me and the people in my life. Even the setting is very much like my world. As I was writing, I was writing about my house, and my little studio in the garden where I work. I had to really examine myself through the process.

JR: It could have been easy to write something about race, to make this a white middle class family, but by making [the New Zealand family and the migrant worker] Indian and Indian, you can see it’s about disparity in class, which I think is actually the biggest problem, this gap that we have in our society between the wealthy and the poor.

DLAR: You spoke about hoping that the play is going to be a kind of mirror, that people maybe see themselves a bit in one of these roles. That leads me into something that is very Indian Ink, which is audience participation. Maybe that’s the wrong word — audience acknowledgement. How do you envision the audience interacting with this play or not interacting with the play?

JL: Fourth wall’s down for a lot of it. If anyone’s seen the Guru of Chai, there’s a storytelling mode which is direct address to the audience, and then there’s a mode where you’re in narrative mode inside the action of the story. You can be in the middle of the action of the story, then pop out to the audience to make a comment about what they’ve just seen, and then dive back into the action. We’ve taken that structure, but we’ve got three tellers instead of one. The audience is invited in, but also allowed to sit back and watch.

DLAR: What kind of physical space design is there? What kind of sonic design?

JL: The space is very — What’s the word? — Impressionistic, expressive of a domestic world. The story all takes place in and around a suburban house with a nice wall around it. The audience is just kind of invited into that, but the whole telling is very plastic and the use of space by the performers is very plastic.

DLAR: Jacob, as a performer, what has the workshopping experience been like?

JR: We’ve got Dave Ward, seasoned composer, who’ll be on stage performing live, which is always a joy. He is so much part of the furniture of Indian Ink now that we have a shorthand with him. His music is absolutely fantastic. We’ve got two young actors, Jehangir Homavazir and Alisha Jacob, and we were in the very privileged position of auditioning them last year, so they’ve been with Indian Ink, learning the vocab of performance, the character expression through the body and voice, and the mask training that we have in our DNA. It’s great for me to see it again through their eyes and then form this ensemble over that time, because that’s what an ensemble needs. It needs time, and we’ve had the luxury of that over the last year.

It feels like it’s built up a real head of steam now, as we get into the final set of rehearsals and into performance. The script feels really sound. It’s really been tested, and there’s a lot of fun with this idea of three storytellers who are not always in agreement.

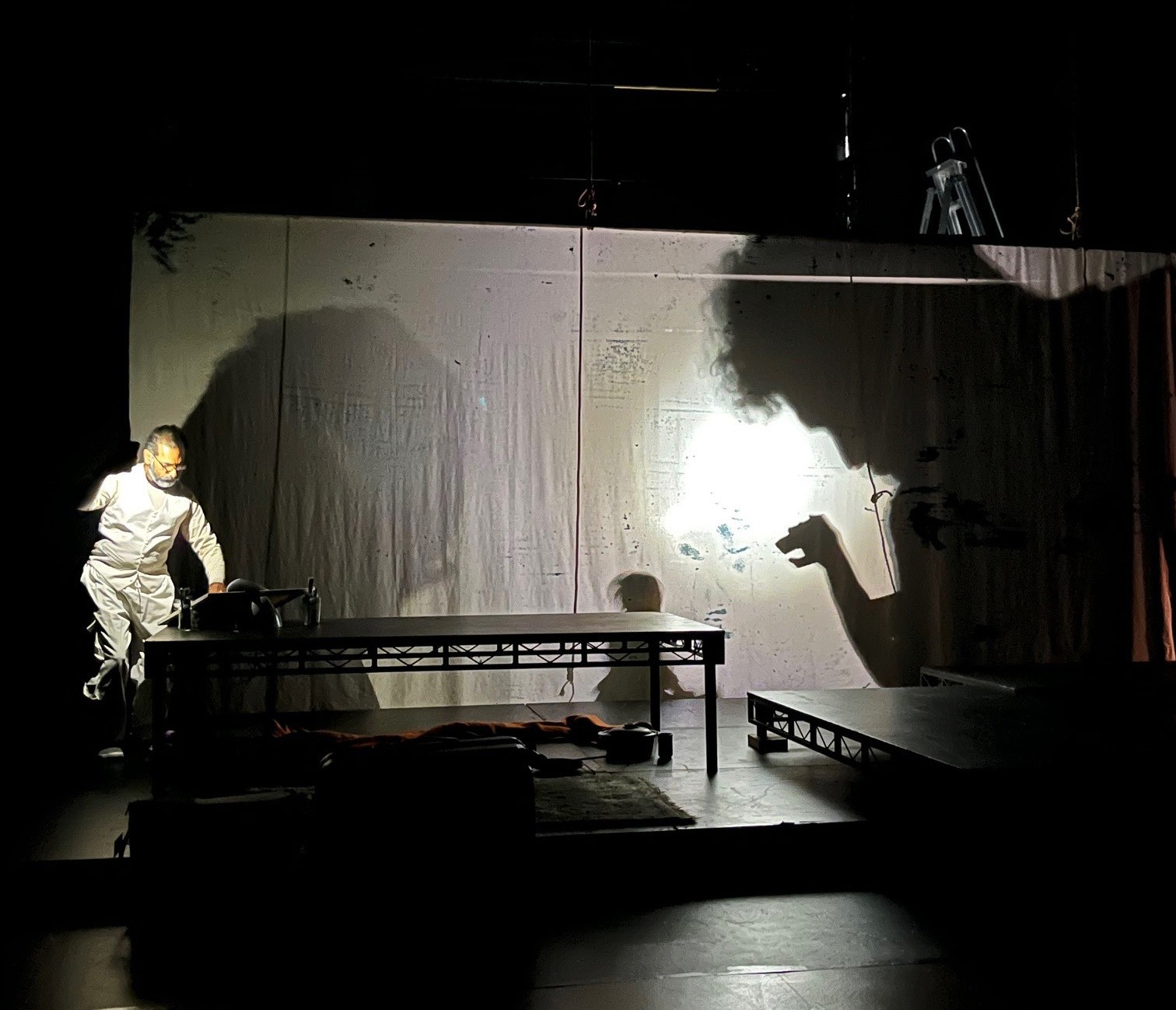

And of course, we’ve got puppetry. We’ve got Jon Coddington, an extraordinary puppeteer, as well as shadow puppetry. There’s a lot of theatricality, and that’s what I go to theater to see — I don’t want to see Netflix on stage, I want to see something that

provokes my imagination. This certainly does that.